Constitution or Tyranny

By Mark Helprin

In fear of a Thomas, Scalia, Roberts, Alito originalist coup de main, and with extraordinary brilliance—for her—Senator Dianne Feinstein recently expressed this view of strict constructionism: "Women would not be provided equal protection under the Constitution, interracial marriages could be outlawed, schools could still be segregated and the principle of one man, one vote would not govern the way we elect our representatives."

Leaving aside the bizarre notion that originalists fail to recognize that Constitutional amendments govern—which, of course, by the Constitution's original command they do—her plaint is only the blunt tip of a long and freighted spear. Quite simply, the Left openly disdains the Constitution when it frustrates even the most transient of their preferences.

For them, it is a benighted 18th-century document that can be interpreted to mean the opposite of what it states, and is best elasticized into meaninglessness, the void of which they cover with a thatch of legislative decrees as thin as needles but as thick as fish in a crowded sea—a forest of forty, fifty, or sixty thousand closely leaded pages in which the fundamental powers of the people are lost and subsumed. This view comports with a Darwinian notion of the evolution of law, as in the English model that we did not choose; with a visceral distrust of tradition; with an interpretation of history that seeks even destructive progression and rejects even benevolent repetition; with hostility to certain principles of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, such as the recognition of rights pre-eminently in the individual; and with a frequently bitter disfavor of impediments to the bureaucratic drive or the immediate expression of popular will.

A case in point is the Left's conviction that the 2000 presidential election was illegitimized by a constitutionally mandated electoral college that weighs votes unequally and thereby begs for abolition. By this logic, so does the Senate. So do the three branches of government, where a party with 51% of the vote may make 100% of the decisions. And so do the states. Is it fair, for example, that the people of Wyoming can make their own law, whereas the people of the Upper West Side must combine their aspirations with those of the primitive inhabitants of the Adirondacks?

In the 19th century, oil was transported in ships with hulls caulked to form a single chamber, and as their cargoes shifted with irresistible momentum these ships readily capsized. Naval architects then compartmentalized them so that their massive loads could not rush unchecked in reaction to the momentary condition of the sea. This is what the founders did in restraining the power of even self-government, and this is what those who recoil from the Constitution as it is actually written find most distressing.

In the name of efficiency, speed, and process, they chafe at those of its elements that frustrate the impulse of the moment, force compromise, or sidetrack action. But without these frustrations, which yet allow an energetic executive to act in time of emergency, we would find ourselves in the presence of the kind of immediate, singular, untrammeled power of, for example, the king that George III might have become had he not been frustrated by the Magna Carta, the Common Law, Parliament, and the Atlantic Ocean.

Though they call it progressive, their vision of governance predates the Constitution and favors the jealous power not of kings but, in their place, a kingly state in which the implicit ownership of all the realm is established not through vassalage but by an unlimited power of taxation, and in which corporate rights are vested not in feudal classes, guilds, aristocracy, and sects, but in race, ethnicity, and sex.

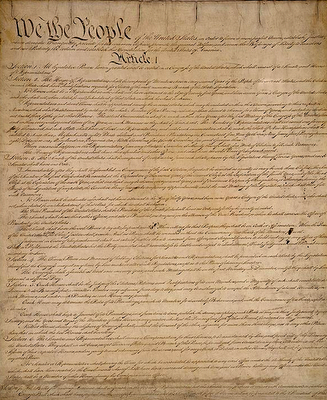

What stands in the way of this retrograde vision that would catapult Western civilization back to the autocracy, corporate rights, and cults of obedience from which it has gradually emerged over several thousand years? The Constitution, as it stands, a document that is by nature clarifying. Metaphorically, whereas the strict constructionist removes the accumulated scale so that original intent can be seen in depth and detail, advocates of a "living" Constitution bury it so deeply in layer upon layer that only the topmost gloss will govern according to the whims of the governors. And lest some jurist incapable of ordering principle over decree be forced to the embarrassment of ruling contrary to his prejudices, and thereby affirming the essence of law, they simply imagine a new Constitution every time they find it standing in the way.

Nor is strict construction, as it is often portrayed, inflexible or passionless, not that these need be disqualifying. Because the Constitution can be amended, it is perfectly flexible, though not hurriedly so. The telling difference between the liberally elastic document and the conservatively amendable one is that the latter demands the consent of the governed rather than that of a small juridical elite. And if the life of the "living" Constitution emanates from the regulatory song of the bureaucratic state, the life of the real Constitution arises in the passion of the Declaration, the First Organic Law of the United States, the minder and conscience of a Constitution ratified in compromise and forced to delay but not to deny the implementation of the Declaration's self-evident truths. The unparalleled language of the Declaration, forged in war, draws its force from its postulates and intent, and its postulates and intent are unequivocal, the guide stars of the nation and its Constitution, as Lincoln, if not Dianne Feinstein, would attest.

And contrary to the senator's thoughtless accusation, it is the originalist view—Lincoln's view, the view of the Union dead—that, in fact, guarantees equal treatment under the laws, the preservation of individual rights, and the continuance of the republican form of government. For with the Constitution as it is actually written, many political outcomes are possible, but with a Constitution that is imagined day by day and hour by hour, all politics are tyrannical.

This article can be found in the Spring 2006 edition of Claremont Review of Books

Mark Helprin, whose books include A Soldier of the Great War and Winter's Tale, is a senior fellow of the Claremont Institute.

No comments:

Post a Comment